- Slug: BC-CNS-Navajo Learners,1670

- Graphics: Navajo-speaking children,enrollment by school type and Native languages (embed codes below)

- Audio clips below.

- Photos available (thumbnails, captions below)

By TAYLOR NOTAH

Cronkite News

WINDOW ROCK – “Béédaałniih: Diné bizaad bídahwiil’aah. Táadoo biligáana k’ehjí yádaalłti’í. Ahéhee’.”

These are the first words that visitors see on a sign at the entrance of Tsé Hootsooí Diné Bi’ Olta’, an elementary immersion school that teaches the Navajo language to its 133 students on the capital of the Navajo Nation.

In English, the sign means, “Remember: We are learning in Diné. Please leave your English outside. Thank you.”

Visitors coming to the school also see trophies. Lots of them. Two full trophy displays line the halls near the entrance and even more trophies sit on top of bookshelves in the library, or naaltsoos bá hooghan, as students and teachers call it.

These trophies are awards that Diné Bi’ Olta’ students have won since the school opened its doors in 2004. Schools on the Navajo reservation compete in annual cultural competitions that include pow wow dancing, singing, Navajo spelling bees and science fairs. Many are Diné Bi’ Olta’ students who have showcased their knowledge of Navajo language and culture, earning the school a reputation well enough to feature previous students in the Navajo-dubbed version of Pixar’s “Finding Nemo,” or “Nemo Hádéést’į́į́.”

“The Navajo language and culture are the backbone of the school,” said Audra Platero, the school’s principal for the past four years. “What continues to make Diné Bi’ Olta’ unique is the fact that we’re a public school. Our teachers are trained and certified to teach Navajo language… and students are exposed to it everyday.”

Platero says instilling Navajo values, culture and tradition within the students can help combat the looming threat on Navajo land: the loss of the Navajo language.

“(Our students are) constantly being exposed to how the language and culture has shifted, and (they) are learning now it’s their responsibility to learn language and culture,” Platero said.

Instilling resilience

Recent studies reveal that the number of speakers who are fluent and understand the Navajo language is declining.

Wayne Holm, a researcher of Navajo language revitalization, has documented how the number of speakers began to decline starting in the 1970s and 1980s. Now, according to surveys administered by the Department of Diné Education’s Office of Educational Research and Statistics, Navajo schools encounter only one or two fluent Navajo students per 1,000.

In an effort to reverse the decline in Navajo language fluency, Diné Bi’ Olta’s classes use different approaches. Each teacher comes from a different area of the reservation, and traditional teachings vary.

Teachings also depend on the seasons and events occurring on the reservation, according to Platero, but some traditions that are passed onto the students include weaving, basket-making and agricultural gardening. Every Thursday, students are encouraged to dress in traditional attire.

Tennell White is a member of the Navajo tribe, and two of her three children go to school at Diné Bi’ Olta.

White said she chose to enroll her children in the school because of the traditional teachings. She grew up in a traditional household in Wheatfields, Arizona.

“(Navajo) is extremely important to me because my family is very traditional, and it is important that my children know (about the language and culture),” White, 34, said. “I don’t want my children to forget where they come from.”

She said her children are fortunate to learn about Navajo customs both at school and at home.

“Their grandma only talks in Navajo, and my kids can communicate with her,” White said. “They can’t carry on a whole conversation, but they know the basics in how to respond and ask questions.”

White also said she noticed her children have gained more knowledge about traditional events that her family frequently attends in the community, such as pow wow dances.

“They know what it is because they learned about these ceremonies at school,” White said. “They understand what is going on; they recognize the songs. To me, that is something that they will carry on and hopefully pass onto the next generation.”

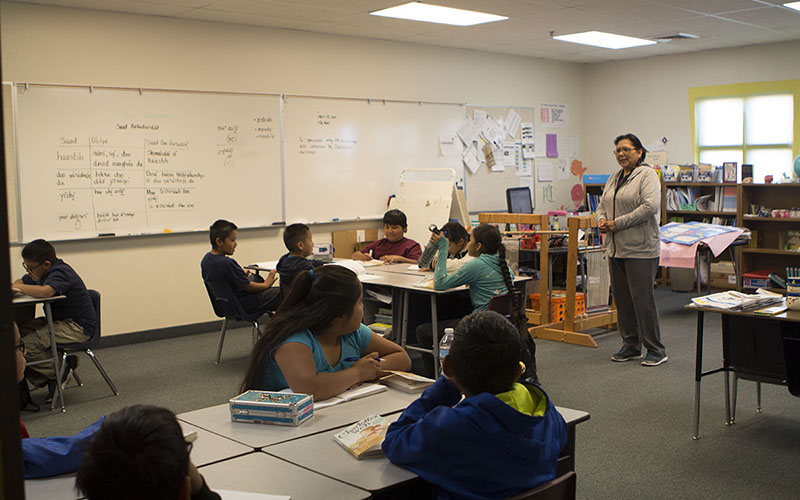

Seeing the passing on of this cultural knowledge is a highlight for fourth-grade teacher Gwendolyn Begaye, who has taught at Diné Bi’ Olta’ since 2013.

“It’s when they finally get something they understand, they make that connection,” Begaye said. “It’s like an innocent understanding, it just falls into place. That’s my highlight.”

Begaye said she saw a student make a connection between lessons on electricity and gender roles in pow wow dancing (where women dance on the inside of the dancing circle, and the men dance on the outside).

“It was really interesting when one of my students said, ‘You know, this is like the female side and this is the male: you have both sides to make that light bulb turn on,” Begaye said, smiling. “That connection was really huge for me. Our language and culture, it ties in with everything.”

A language dwindling in speakers and support

Despite a renewed emphasis on language preservation, schools that offer Navajo language and culture courses meet opposition from some parents, many of whom were raised in traditional Navajo households and even speak Navajo fluently, according to Tommy Lewis Jr., the superintendent of schools on the Navajo Nation.

“A lot of the time, we get into a dispute at the school level. Some parents say, ‘I don’t want my child exposed to the Navajo language. It won’t do them no good. They need to know English in order to survive in this world nowadays.’” Lewis said.

Begaye said this opposition is a barrier when it comes to effectively instilling Navajo within the students. Without language reinforcement at home, Begaye said she takes every opportunity to incorporate the Navajo language into her class of 13 students.

“Not all of them come from a home where Navajo is being used, and it’s hard,” she said. “Sometimes it makes us as teachers to think about school as a last resort to pull them back into the language and culture.”

Having a rounded education in the Navajo language can increase cultural understanding which in turn, Lewis said, helps to build resilience among students.

“(Knowing Navajo) builds up your self-confidence, your understanding of responsibilities, understanding of strength and determination,” he said. “That’s what Navajo teaches us.”

He said the future of Navajo culture is at stake.

“What happens then? (Navajo) is going to be part of the melting pot; there’s going to be no distinct identity,” he said. “Yeah, we might have a tsiiyééł (a traditional hair bun worn by the Navajo people), wear moccasins, but that’s not enough. What about the word? The word is what makes you Diné.”

Lewis said traditional upbringing made him fluent in Navajo, and he said many young Navajos do not have that opportunity today because of an earlier push for western education.

“The goal was to make us civilized Indians,” Lewis said of federal programs. “How our people sacrificed their life, their freedom, their culture, by their way of life because of this education. I agree it’s good, but education also is dangerous. A lot of our people lost their language and culture because of it.”

Previous tribal and federal attempts at Navajo education in schools have proved ineffective. The federal No Child Left Behind law pushed cultural education to the back burner. The tribe’s Navajo Sovereignty in Education Act of 2005 promised more Navajo education, but Lewis said schools rarely followed suit.

Seeking to implement more effective measures, the Department of Diné Education initiated a new law called the Diné School Accountability Plan which Lewis describes it as a new approach in Navajo education that focuses Diné content standards as a centerpiece.

“The main thrust (of the plan) is our language, our culture, our history, our government,” Lewis said. “The public schools here on Navajo resist, and how do we penalize it? We don’t have any enforcement powers unless we change the laws, and the Accountability Plan is going to test that.”

Though the DSAP only applies to Bureau of Indian Education schools on the reservation and not Diné Bi’ Olta’, Lewis said the intention is to instill Navajo content and standards to all Navajo students attending school on the reservation.

Promoting self-identity for the future

Though the school often faces obstacles such as changes of vision in school administration and the lack of parent involvement, school funding, small student enrollment numbers and abiding by Arizona’s education mandates, Platero said her focus is making sure teachings are always being passed down to the young Navajo generation.

“I want to ensure that today and tomorrow our students are learning their language, their culture, they’re learning about self-identity and they’re having the ability to function in both worlds,” Platero said. “It’s not just about western academics here. They’re always learning about themselves.”

When Begaye looks at her class, she said she dreams that Navajo education as a whole will progress for Diné children.

“I would love to have each one of my students to go onto college. I tell them, ‘Yéego, ínít’į’ (Try your best). I am here to help you. Ask me questions, and don’t be afraid,’” Begaye said. “That’s where I wish our leaders would really invest in our kids’ futures and that, hopefully, one day, Navajo education is going to encompass everything. We’ll have more colleges where they’re challenging our students and they’re getting them ready to explore life out in space. That’s what I want for my students.”

As Lewis makes frequent visits to schools across the Navajo Nation, he said he is always astonished when students greet visitors with prayers spoken entirely in Diné bizaad (Navajo language) and exhibits Diné values. He commends those schools, noting Diné Bi’ Olta’ as an example of Navajo instruction working for Navajo youth and he urges for more Navajo families to reconnect with their language and traditions and to continue passing on these teachings to the young ones.

“Language and culture is about survival,” he said. “It brings pride, joy and happiness in your life when you know your language. It’s about decency, resiliency, being strong, determined, understanding nature and the natural order, how the world is made. Where do we fit into this world as human beings? That’s how powerful it is.”

^__=

Click and listen:

Click on the terms below to hear them pronounced in Diné, the Navajo language.

_ “Béédaałniih: Diné bizaad bídahwiil’aah. Táadoo biligáana k’ehjí yádaalłti’í. Ahéhee’.” (“Remember: We are learning in Dine. Please leave your English outside. Thank you.”)

_ Tsé Hootsooí Diné Bi’ Olta’

_ Diné

_ Naaltsoos bá hooghan (Library)

_ “Nemo Hádéést’į́į́” (“Finding Nemo”)

_ Tsiiyééł (Traditional hair bun)

_ ‘Yéego, ínít’į’ (Try your best)

– Audio recording of Navajo phrases by Diné Bi’ Olta’ student Star Parkhurst and Cronkite News reporter Taylor Notah

^__=

_ Navajo-speaking children embed code: <script id=”infogram_0_taylor_notah__enterprise” title=”Navajo language knowledge in youth” src=”//e.infogr.am/js/dist/embed.js?93C” type=”text/javascript”></script>

_ School enrollment embed code: <script id=”infogram_0_tnotahs_enterprise_draft” title=”TNotah’s enterprise draft” src=”//e.infogr.am/js/dist/embed.js?krx” type=”text/javascript”></script>

_ Native languages embed code: <script id=”infogram_0_taylor_notah__enterprise-3″ title=”Most common Native American languages in North America” src=”//e.infogr.am/js/dist/embed.js?pBm” type=”text/javascript”></script>

^__=

A seal of Diné Bi’ Olta’ created by students is displayed in the school’s library in Window Rock. The K-6 immersion school incorporates the Navajo language and culture into its curriculum. (Photo by Taylor Notah/Cronkite News)

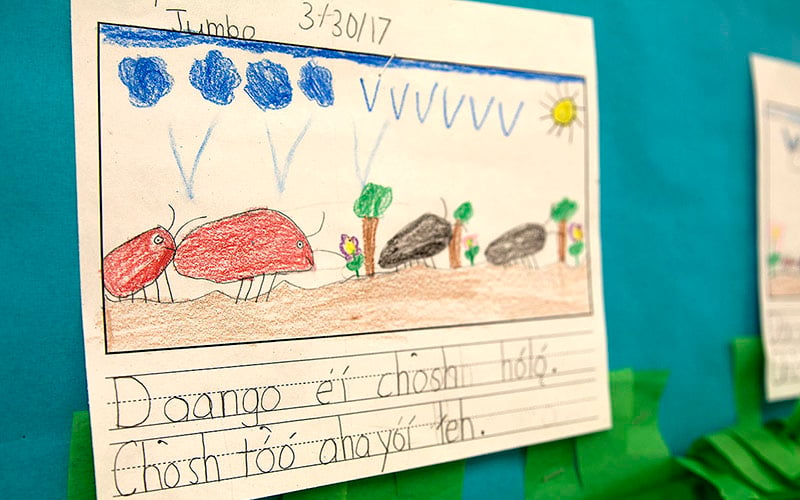

A student’s drawing hangs in the hall at Diné Bi’ Olta’ in Window Rock. Many assignments like this are written entirely in the Navajo language. (Photo by Taylor Notah/Cronkite News)

Kindergarten students begin their school day with one hour of Navajo instruction. (Photo by Taylor Notah/Cronkite News)

Language continuance efforts are not only taking place in Navajo classrooms but in communities as well. A stop sign located near the Navajo Nation Museum in Window Rock shows the Navajo word “áłtsé,” which translates to “wait first.” (Photo by Taylor Notah/Cronkite News)

Audra Platero, the principal at Diné Bi’ Olta’ and fluent speaker of Diné bizaad, said Navajo language and culture is the backbone of the school. (Photo by Taylor Notah/Cronkite News)

Gwendolyn Begaye, a fourth-grade teacher at Diné Bi’ Olta’, discusses “Charlotte’s Web” with her class. Instructors are encouraged to speak Navajo to students in every subject every day. (Photo by Taylor Notah/Cronkite News)

Tommy Lewis, Jr., the superintendent of schools on the Navajo Nation, said he fears the Diné language will disappear in 25 years if tribal leaders, educators and parents don’t take action. (Photo by Taylor Notah/Cronkite News)

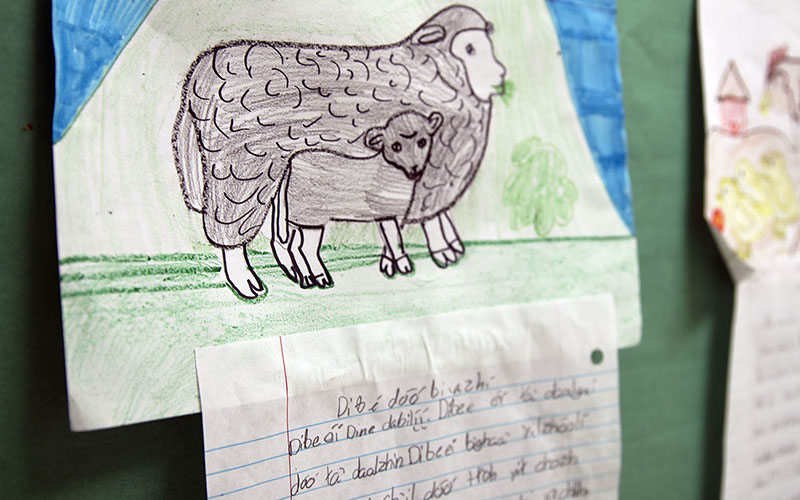

Titled “Dibé dóó biyazhí” (“The sheep and its young”), a student’s drawing hangs in the hallway at Diné Bi’ Olta’. (Photo by Taylor Notah/Cronkite News)