- Slug: BC-CNS-Navigating Narcan,1520

- Video interviews with Moak, Patterson and Miller available.

- Photos available (thumbnail, caption below)

By COURTNEY COLUMBUS

Cronkite News

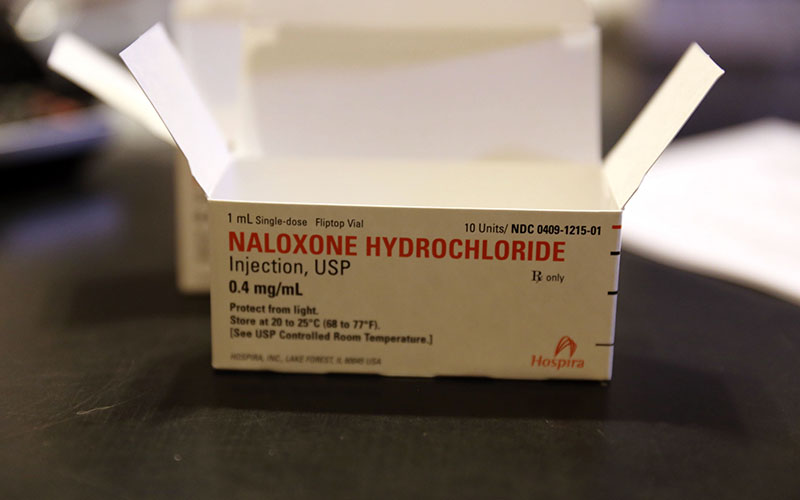

Arizona enacted a law last year allowing the purchase of the opioid overdose reversal drug naloxone without a prescription but training for pharmacists, and the state Medicaid program’s inability to cover the cost without a prescription have slowed access to the drug.

Naloxone under the brand Narcan, when administered during an overdose, can save lives. And, it has no effect on someone who is not overdosing so there is little chance for abuse.

“It’s quite effective in stopping an overdose if you get to them in time,” Tucson Police Lt. Christian Wildblood said. “I’ve seen people that look like they were on the verge of death, they were actually turning purple and gray, their blood was settling,” he said. “I’ve seen them (paramedics) give them Narcan, and within 10 seconds, they’re awake and jump back to life. It’s one of the wildest things I’ve seen in law enforcement.”

Pharmacists who dispense naloxone without a prescription must first be trained on how and when the drug should be used — a process that began in December. But it is not mandatory for pharmacists to enter the process.

The law also enables nonprofit organizations to host naloxone trainings and dispense the drug to community members. Since it started distributing naloxone kits in September, Sonoran Prevention Works said it has documented 260 overdose reversals.

Debbie Moak, director of the Governor’s Office of Youth, Faith and Family, focuses her efforts on substance abuse prevention, but also sees naloxone as an important tool in the battle against the opioid epidemic.

“We must utilize every tool available to save people’s lives. Strategically, naloxone, brand Narcan, is the best tool we have available, the only tool when someone has overdosed to save their life,” Moak said. “We need to make sure that the average citizen, especially those who are being prescribed an opioid, the family and friends, they also need to know how to use this.”

‘Stop death in its tracks’

Last year, Tucson Police Department officers started carrying naloxone. The agency spent about $28,000 for 700 doses of the nasal-spray version of naloxone — about $40 per dose.

Wildblood, who works for the department’s Counter Narcotics Alliance, said he saw drug addicts in the throes of an overdose, on the verge of death, when he was a patrol officer in Tucson.

“Fast forward 10 to 15 years, to where we’re at now, and now cops can administer it,” Wildblood said. “It’s amazing to me to think that we’ve come this far with this drug and being able to save people that much quicker. So, in the past, you know, you just had to wait for the paramedics to show up.”

Wildblood said an officer used naloxone to reverse an opioid overdose just a few weeks after the department went through training.

Expanding access in Arizona

The Secretary of State’s office published an emergency rule in January that listed details about the training that pharmacists must receive before they can dispense naloxone without a prescription. Among the requirements: pharmacists must educate the people they give naloxone to about how to prevent and recognize opioid-related overdoses and how to administer naloxone. They must also emphasize the importance of getting emergency medical treatment for the person suffering from an overdose.

The Arizona Pharmacy Association, which provides continuing education to pharmacists, posted a training webinar on Dec. 16 that meets the requirements outlined in the rule. The association’s CEO, Kelly Fine, said in an email that 170 pharmacists out of the 7,220 licensed pharmacists in the state had registered for the training as of Feb. 9.

“The more pharmacies we can get trained, the more pharmacists who can dispense it, the better,” Fine said. “We’re very excited and encouraged to get the word out.”

But just because pharmacists take the training doesn’t mean their pharmacies will immediately start dispensing naloxone without a prescription. Pharmacists that are interested in providing naloxone will have to get approval from their corporate offices, Fine said.

Pharmacists can also take the training through their employers, as long as it meets the requirements in the rule. Completing the pharmacy training through the Arizona Pharmacy Association also earns them continuing education credits, Fine said.

Some nonprofit leaders also plan to help train pharmacists.

Angie Geren, executive director of the nonprofit Addiction Haven, said she plans to organize groups of volunteers to visit local pharmacies and provide the training to pharmacists.

“The hardest part is to get the information out,” Geren said.

Susannah Castro’s 19-year-old son, Cree, died of a heroin overdose in 2015. She founded The Cree Project, a nonprofit that provides education and outreach about prescription opioid and heroin addiction. One of the website’s pages showcases photos of Cree dating back to his early childhood. There is only one sentence on the page: “We remember you.”

Castro applauds the recent efforts to expand access to naloxone in Arizona.

“When I first started, I was appalled. When Cree was having his problems, I didn’t know that I should have naloxone, I didn’t even know what it was. We’re seeing some good progress,” Castro said.

George Patterson, 25, credits a dose of naloxone with saving his life during an overdose. He started taking oxycodone pills at 21, which soon led him to heroin. He wanted to quit, but couldn’t. He went to a rehab center for treatment, but relapsed.

Patterson now volunteers for Sonoran Prevention Works, helping to pack up kits of naloxone that the nonprofit organization distributes across Arizona.

Jessika Miller, who helped Patterson put together naloxone kits at his home in Mesa last month, said she always carries naloxone with her.

“You just never know when that moment’s gonna come where it makes a difference,” Miller said.

She said she has never needed to administer naloxone to someone, but there are times she wishes she would have had it. The drug is available in nasal-spray and injectable forms. If someone administers naloxone to a person who isn’t overdosing on opioids, the drug won’t affect them. Community members who administer naloxone to someone who is overdosing can’t be held liable for damages, according to the law passed last year.

Insurance coverage

The state’s Medicaid insurance, the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System, currently doesn’t cover the cost of naloxone for people who buy it without a prescription because of a conflict between the new naloxone access law and another state statute. This conflict could be a problem for private insurance companies as well, said Dr. Kam Gandhi, executive director of the Arizona Board of Pharmacy.

“We can only dispense medications that are ordered under a prescription. The way the state law is, it’s being dispensed without a prescription,” said AHCCCS deputy director Beth Kohler.

AHCCCS is working with the Arizona Pharmacy Association to find a solution that would allow them to cover the cost of naloxone for people who buy it at pharmacies. Sources said the cost of naloxone can range from free (in the case of kits distributed by NGOs) to more than $1,000. In May 2016, Politico reported that the costs of some forms of naloxone had increased by up to 17 times in the past two years.

Two possible options include the creation of a standing order that would essentially serve as a stand-in for a prescription, or to give pharmacists prescriptive authority – meaning they could write prescriptions for people who come to a pharmacy to buy naloxone, said Gandhi.

“We’re obviously supportive of efforts to get naloxone widely distributed,” Kohler said.

She said AHCCCS administers state substance abuse grants and recently gave a $500,000 grant to Sonoran Prevention Works to distribute naloxone and train community members how to use it.

Haley Coles, the executive director of Sonoran Prevention Works, led a training session about opioid overdose reversal at the Navajo County Health Department in Show Low.

Coles emphasized that use of naloxone fits into the harm-reduction model, which differs from a strictly prevention-based approach to the opioid epidemic. Naloxone can save people’s lives, but not necessarily stop them from using drugs.

“A person’s really vulnerable after an overdose, and that might be an opportunity to help them get treatment, if that’s what they want,” Coles said. “It might be an opportunity for them to get attention for the chronic pain that they’ve been using opiates to deal with. So there’s a lot of things we can do for a person that’s just experienced an overdose, as long as we’re not being coercive.”

She travels the state doing similar trainings and focuses on getting naloxone into the hands of people who are actively using drugs.

Coles and Patterson said they still hear myths about ways to save a person who has overdosed on opioids. But the myths can actually cause harm. Examples: burning the person’s feet and putting ice down their pants.

Patterson now works at The River Source, a substance-abuse treatment center in Mesa. He plans to continue helping to get naloxone out into the community.

“It’s the reason I’m alive today. If you say getting naloxone into the hands of people that are actively using isn’t important, then you’re saying my life isn’t important. And I help people today, and I love people today, and I’m a contributing member of society.”

^__=

Naloxone hydrochloride, commonly sold under the brand name Narcan, reverses the effects of opioid overdoses. (Photo by Courtney Columbus/Cronkite News)

Sonoran Prevention Works said it has documented 91 overdose reversals since Jan. 1 from naloxone kits given out in Arizona. (Photo by Courtney Columbus/Cronkite News)