- Slug: Borderlands-Uvita. 2,340 words.

- Photos, charts available (thumbnails, captions below).

By Carly Stoenner

Cronkite Borderlands Project

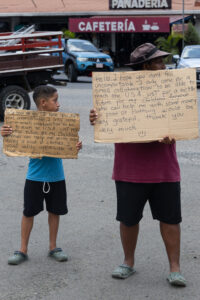

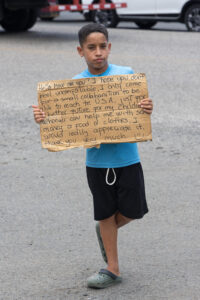

UVITA, Costa Rica — Yocelin Dayana Garcias Barrio and Gladys Yusberny Seijas Matute stand begging for money in front of a grocery store in this small tourist town on the Pacific coast in southern Costa Rica. They hold pieces of cardboard with messages written in black ink. The 90-degree tropical sun bears down on them, and perspiration mixed with highway exhaust soaks their clothes. They have been on the road for two months since leaving Colombia, which was their first stop after fleeing their home country of Venezuela.

“We are a Venezuelan family. We are migrants. Please help us if you can with work, food or a little money,” reads their makeshift sign. “Thank you from the bottom of our hearts.”

The store is a BM SuperMercado that sits next to highway 34, about 83 miles north of the Panamanian border. This is in the heart of Bahía Ballena, a rural district with an estimated population of around 3,300. For two years, large numbers of migrants have either moved through or stayed in the district’s small towns and villages to work or solicit money to continue their travels.

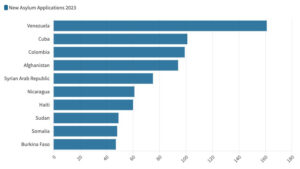

In September 2024, an average of 865 migrants a day arrived in Costa Rica, according to the United Nations’ International Organization for Migration (IOM). Most of the migrants coming into the country are from Colombia, Venezuela and Ecuador – and most of them enter from Panama. Those who don’t have immediate transportation north often gather at stopovers along the highway, like the SuperMercado parking lot. On some days, up to 10 families with children can be seen carrying signs and asking for change from customers.

According to IOM, migrants moving into Costa Rica from Panama surged to around 84,000 in August 2023, prompting Costa Rican President Rodrigo Chaves to declare a state of emergency on Sept. 29, 2023. Weeks later, the Costa Rican and Panamanian governments created a plan to transport migrants by bus from the Darién region in southern Panama to Costa Rica’s border with Nicaragua. The trip costs migrants $30 per person. A small percentage are granted free passage under a “humanitarian” program. According to Costa Rican officials, busing the migrants north has reduced refugee camps and relieved tensions at the border with Panama. Officials also claim it’s a safer alternative to human trafficking organizations.

For some migrants and their families, however, the $30 bus fare is out of reach. Most migrants who cannot afford a ticket must wait at the temporary attention center for migrants, known by its Spanish acronym CATEM. It’s located just north of the Panamanian border. For those like Garcias and Seijas, who have no financial support, it’s nearly impossible to pay for the bus ride. After four days inside CATEM, they said they escaped the facility by jumping a barbed wire fence when the guards weren’t looking.

“They lock us up there as if we were criminals, the food is not enough, and they keep us there until they feel like sending us [to Nicaragua],” Garcias said.

IOM estimated that between January 2023 and October 2024, there were an estimated 58,000 migrants living outside of shelters in Costa Rica.

Roberto Blanco is the project director of Alianza VenCR, a humanitarian aid organization that helps Venezuelan refugees apply for asylum and to integrate into Costa Rican society. He said the official migrant buses are administered by the immigration police, and supported by the United Nations Refugee Agency, UNHCR.

“In some way, the pressure on all the services of the country decreased a little, and we believe that it is and has been an effective and positive action that supports the safe transit of migrants so that they continue their journey,” Blanco said.

It is unclear how the policies of Donald Trump, who was elected to a second term as U.S. president on Nov. 5, will affect the flow of migrants.

According to Costa Rica First Vice President Stephan Brunner, the Costa Rican government has received mixed messages from President Joe Biden’s administration.

“Sometimes they don’t want to have these migrants on the Mexican border, but then Biden says you will all be welcomed,” Brunner said in an interview in March. “And then we don’t know exactly what they’re expecting from us.”

Crossing the Darién Gap

Migrants like Garcias often arrive in Costa Rica mentally and physically wounded from crossing the Darién Gap, a 66-mile stretch of tropical rainforest that separates Colombia from Panama.

“Look, it’s psychological. You have to be mentally prepared because there are people who are weak-minded and look for an easy way out. Some commit suicide, others are unlucky and fall down the ravines,” Garcias said. “We saw a lot of dead bodies thrown on the ground. If someone dies, they leave the bodies there lying there like dogs. The only thing you can do is wrap them and leave them there.”

According to the Panamanian government, more than a half million people crossed the Darién Gap in 2023, double the number of crossings from the previous year.

In May, UNICEF estimated that 800,000 people might cross the Darién Gap in 2024, including a record high number of children. In July, newly elected Panamanian President José Raúl Mulino took steps aimed at shutting down immigration through the area, and Panamanian officials reported a decrease in the number of crossings.

Garcias said she witnessed abuse by border enforcement officials in Panama.

“The Panamanian government officials rob migrants, they rape the girls, they take your money. It’s a desperate situation,” Garcias said. “There’s no order.”

Edgar Pitti, inspector general for the Panamanian border protection service SENAFRONT, has said in interviews and public statements that his agency provides humanitarian help to migrants and works to protect them from criminals.

Why there are so many migrants in Uvita

The Tracopa bus terminal sits just across the highway from the BM SuperMercado where migrant families hold signs asking for food and money. Sister Reina Perla, a Catholic nun, is handing out hot meals to migrants arriving at the terminal on the bus from the government immigration center known as CATEM. The bus terminal in Uvita is the first stop for migrants who are being carried north on the government-chartered buses. Here the migrants are given 30 minutes to get off the bus, buy food and go to the bathroom.

On this day in March, the nuns have prepared 300 free meals – but that is not always enough to feed all of the arrivals. The meal service is financed by Adveniat, a German Catholic humanitarian aid organization.

“We saw the opportunity to help with food. It’s a complete hot meal,” Perla said. “We know that they come here without having eaten anything prepared, only packaged food, for days, or sometimes without eating anything at all.”

According to Perla, the service is an important moment of respite for those who may have recently emerged from the Darién jungle. She said many of the families have not had the dignity of sitting at a table with chairs and sharing a warm meal with their family in weeks. After the meal, the migrants receive a personal hygiene kit with towelettes, toothbrush and toothpaste, shampoo and soap.

Perla said most migrants who arrive on foot in Costa Rica have crossed the Darién Gap and decided to walk north through Panama.

“At times they can take a bus, but only a short distance according to what they can pay,” Perla said. “They sleep in the street.”

Perla said if immigration officials see a group of migrants on the road, they load them onto buses and take them to CATEM. If the migrants can’t afford the ticket north, they have to wait at least 15 days for a chance to catch a free “humanitarian” bus. According to Perla, migrants without money must earn their ride by performing some type of job inside the shelter, such as cleaning. Only certain NGOs are allowed inside, like the Red Cross and the UNHCR. The Cronkite reporting team was not allowed access inside.

“The benefit of CATEM is that the migrants are not on the street. They have a roof over their heads and they are safe,” Perla said.

2 brothers seek better opportunities in the U.S.

Two migrants who received a hot meal at the bus station were Juan Camilo Orjuela Patiño, 23, and Juan Miguel Orjuela Patiño, 26, brothers from Colombia. By the time they arrived at the Uvita bus terminal, they had been traveling for a week. They weren’t part of the official bus passengers from CATEM to Nicaragua but showed up on their own from Panama. They said they were trying to move fast, avoid the authorities and reach the U.S. as soon as possible.

“There’s a lot of people that leave the shelter because it’s very expensive. For people that cross the Darién, it’s very expensive,” said Juan Camilo. “Just to pass, it’s $160; you get to a shelter, it’s another $60; another center and it’s an additional $80. Another $40 here and $40 there and so on. It’s a lot of money.”

The brothers are from Valle del Cauca and began their journey by sea in Buenaventura, the largest seaport in Colombia. The brothers didn’t have to cross the Darién on foot. Instead, they paid for a boat to bring them to Panama. Fearing crossing the Darién, they said they were lucky enough to have passports and the knowledge of how to bypass the jungle.

Juan Camilo is a carpenter who makes furniture, doors, cabinets and houses. Juan Miguel is a trained heavy equipment operator and drives backhoes, forklifts and excavators. Their goal, they said, was to make it to Orlando, Florida, for work.

Their mission was to traverse Costa Rica in a single day, paying the $15 commercial bus fare from Uvita to the capital, San Jose, and from there to get a bus to the border with Nicaragua.

“If they [migration officials] caught us here, they would fine us $1,000 and take us right back to the border,” Juan Camilo Orjuela Patiño. “So we are going incognito.”

The brothers said there’s little economic opportunity where they’re from, due in part to the immense pressure from the mass migration of Venezuelans into Colombia. According to IOM, 2.8 million Venezuelans were living in Colombia as of January 2024.

“For example, I’m a carpenter — if you say build me a kitchen, and I quote you $1,000, and out of curiosity you ask a Venezuelan, and he says he’ll do it for $500, who would you prefer to do the job?” Juan Camilo said. “There are so many Venezuelans you don’t even know who is Colombian.”

According to the brothers, they come from an area in Colombia where you can’t trust anyone, a place that is controlled by armed guerillas, that’s very violent and corrupt. This is partly why they feared going to CATEM, traveling with other migrants or taking the official buses.

“People are deceitful. I’m scared that they will deport us,” Juan Camilo said.

Applying for asylum in Costa Rica

In February 2023, the Biden administration announced it would deny most asylum applications from people who arrived at the U.S. border without first requesting asylum or refugee status in a country they passed through.

During his first term as president, Trump put diplomatic and economic pressure on countries to stem the flow of migrants to the United States, and is expected to do so again in his second term.

According to UNHCR, Costa Rica has become a top destination country for migrants in Latin America, currently hosting nearly a half-million people from other countries. Most of Costa Rica’s foreign-born population is from neighboring Nicaragua, which is suffering a political and economic crisis.

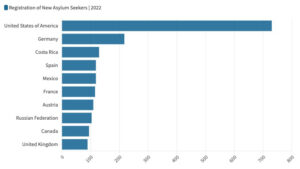

According to the UNHCR 2022 Global Trends report, Costa Rica was the third largest recipient worldwide of new individual asylum applications in 2022, preceded only by the U.S. and Germany. Costa Rica, a relatively small country with a population of 5 million, received more refugee applications in 2022 than Spain, with 47 million inhabitants, and Mexico, with 126 million inhabitants.

Most of Costa Rica’s 129,000 new asylum applications in 2022 were from Nicaragua, stemming from a mass exodus after a bout of severe political repression in 2018. According to the UNHCR, approximately 30,000 Venezuelans are living in the country, but only an estimated 8,774 are seeking asylum in Costa Rica.

Blanco, the project director at Alianza VenCR, is a Venezuelan who migrated to Costa Rica eight years ago. His work focuses on preventing the spread of xenophobia and promoting a narrative of positive migration, or a migration that supports the development of the host country. That’s why Alianza VenCR helps with migratory regularization and humanitarian assistance, but also with skills training for gainful employment as well as support for physical and mental health issues.

“We have had the experience that even when we have reviewed cases of pregnant women or other vulnerable persons, and we have offered our services in one way or another at the level of legal assistance or humanitarian assistance, people have repeatedly stated that it is not their interest to stay in Costa Rica or any other country of transit. Their main interest is to get to the United States,” Blanco said.

According to Blanco, the system in Costa Rica is so oversaturated that there is an eight-year backlog to process asylum claims. However, while they wait for their cases to be heard, asylum seekers are granted a regular migration status, meaning they can work, have free movement and will not be sent back to their country of origin. But for most migrants, Costa Rica is not their final destination — the United States is.

“All of these countries have the same situation. It’s only a matter of time before every Latin American country falls and becomes like Venezuela,” Garcias said. “We are focused on getting to the U.S., we aren’t straying to any other country, and we aren’t getting distracted from our goal. We don’t want to live in any other country.”

For more stories from Cronkite News, visit cronkitenews.azpbs.org.