- Slug: Sports–Life After Football, 1,860 words.

- 2 photos available.

By Dylan Ackermann

Cronkite News

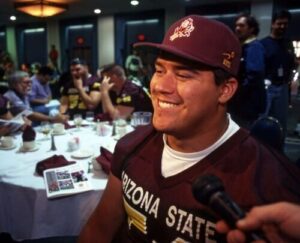

TEMPE – Heading into the 1997 NFL Draft, former Arizona State offensive tackle Juan Roque felt superhuman.

Selected in the second round, 35th overall, by the Detroit Lions after leading Arizona State to an 11-1 record and a Rose Bowl appearance, the two-time first-team All-Pac-10 selection and consensus All-American was certain his best days were still ahead of him.

What many Lions fans remember as one of the most unforgettable Thanksgivings ended up being just as memorable for Roque, although for very different reasons.

It came down to one play that changed everything – Roque’s career was not only never the same, but essentially came to an end.

During a comeback 55-20 win that saw the Lions reverse a 17-3 deficit to beat the 2-10 Chicago Bears, Roque suffered a serious left knee injury that sidelined him for the remainder of the 1997 season and all of the following year.

The injury’s effects lingered, limiting Roque to just four games in 1999. His NFL career ended after that season. He was only 25 years old.

“I equate it to having a death, because football literally does become part of you,” Roque said. “It becomes part of your life, it becomes part of your being.”

When the game writes a player off, letting go is hard. For many, the longing for it never fades.

Grayson Kimball, a psychology professor at Northeastern and a mental performance coach in the greater Boston area, identifies three common ways a career typically ends: by free choice, where athletes walk away on their own terms; through injury; or simply because a player is considered too old or teams no longer want them.

“Many individuals have spent their whole life building and focusing on their sport,” said Misty Buck, an athlete mental health and performance coach. “In sports, there’s not really a lot of time to focus on a lot of other things. They know it’s a good idea to preemptively begin to look at other business opportunities and there’s programs out there to help players with that.

“It doesn’t at all ease the part of figuring out, ‘Who I am?’”

A sport can become more than what an athlete plays. It can define who they believe they are, accompanied by a feeling of invincibility.

“We athletes don’t think it’s ever going to end,” Roque said. “We think that we’re superhuman, that we can overcome anything.”

When it ends, Roque explained, an athlete experiences a shift from being the center of attention – where everyone loves you, buys you drinks, wants to take pictures – to suddenly feeling like a “nobody.”

“If you are a professional or high college-level athlete, you’ve been essentially the center of attention for as long as you can remember,” Kimball said. “When you were in middle school and high school, you set all these records and everybody came to watch (you). Then, you get recruited and even at the pro level, you may not be the best player, but you’re still pretty darn good.

“Now, all of a sudden, nobody’s watching… None of these guys just want to be forgotten.”

Despite how unrealistic it was to make it back to the NFL, Roque continued telling himself he would eventually overcome the injuries. The reason: he couldn’t shake the feeling of missing the game-day atmosphere and camaraderie of a locker room.

That led to his attempted comeback with the Toronto Argonauts of the Canadian Football League in 2001. Unfortunately, it didn’t last and Roque’s playing career came to an end in 2002 after just seven CFL games.

All of a sudden, Roque, like many others, found himself in a position where he felt he had no skills or qualifications for a desk job and had not prepared for life after football.

It all happened so quickly that Roque spiraled into darkness, culminating in his arrest for carrying a concealed weapon, operating a vehicle under the influence of alcohol and felonious assault for pointing a gun at a couple.

“You’re so hell bent on football and then you have to go through the mourning of no longer playing,” Roque said. “It becomes extremely hard. It led me down the path of alcohol and drug abuse. It eventually led to my arrest and eventual conviction of a crime. In my state of mind, I reacted in a way that victimized two people that didn’t deserve it.

“As a result, I had to pay a price, and I had to lose my freedom for a little bit. That’s the price I had to pay for not being prepared for the sport to end. I deserve what happened to me, I was not a victim. I screwed up and I paid the price for it.”

While Roque’s house was in foreclosure in Michigan, someone stepped in to help. In the midst of discussions about how to save his home, Roque was offered a job in the mortgage business.

It may not have been what Roque envisioned in his late twenties, but it was one of many signs that he needed to further his knowledge beyond football.

The final sign came with the death of his former teammate, Pat Tillman, who had walked away from a professional football career with the Arizona Cardinals to join the elite Army Rangers in the wake of the 9/11 terror attacks.

Tillman was killed by friendly fire during a firefight in Afghanistan.

“When he died, it really opened my eyes, making me wonder what exactly I was doing,” Roque said. “Here one of my teammates just made the ultimate sacrifice. He did a selfless act, joining the military and leaving the NFL behind. Now he is gone, and I would never see him again.”

Roque knew Tillman would have scolded him “with very colorful language” about the decisions he’d been making.

During a heartfelt conversation with his ASU coach, the late Bruce Snyder, Roque sobbed, reflecting on the toll it had taken on him. He realized he was nowhere near setting the standard.

Sharing everything that had been happening in his life, he remembers Snyder simply saying, “You need to get back to one at a time.”

“One at a time” was the mantra of that 1997 Rose Bowl team that starred Jake Plummer, Tillman and, yes, Roque.

Without rehab, Narcotics Anonymous or the Twelve Steps, Roque stopped the drugs and, eventually, the alcohol.

“I’m at nine years, eight months,” Roque said. “But at the end of the day, it came down to getting back to what made me successful. Getting back to that athlete mentality. Getting back to that competitive mentality. We have success in us. Even though we’re in the darkness, we already know what it takes. We just got to draw it out.

“You just have to change the sport, and that’s your new career.”

Today, Roque, who joined Phillips Law Group in 2007 with little knowledge of the law, has risen to the position of Intake Manager and Referral Coordinator.

Buck, the mental health and performance coach, acknowledges that there isn’t a single reason that can be blamed for former athletes such as Roque struggling after their playing career ends. But she believes the issue often runs much deeper than merely missing the competitiveness of the sport.

“It might be this is a journey that has taken my family from one place, and now I support my entire family,” Buck said. “I brought my entire family to a new way of living. I’m creating generational wealth. Other athletes, it may have been their outlet for so much of their life and the things they dealt with or even just where they feel most like themselves.

“It’s often more layered than you may think.”

Former Sun Devil quarterback Steve Campbell, who was teammates with Roque during the 1995 and 1996 seasons, realized from a young age that coaching was his destiny.

Thanks to his father, Gary, who coached Steve at Norco High School in California and finished his high school coaching career with 276 wins, Campbell enrolled in ASU without questioning what his major would be.

Yet, that still didn’t make leaving football any easier.

“When I have dreams, even now at my age, it’s about playing still,” Campbell said. “It’s not about coaching.”

Coaching at Williams Field High School in Gilbert still provides Campbell with many of the same feelings he experienced as a player: a sense of community, competition, camaraderie, and strong relationships.

Still, it hasn’t replaced the experience of being on the field for Campbell, who longs for the feeling of having the ball in his hands and influencing the outcome of a game.

“The common thing everyone says, not only in sports, is ‘what I would give,’” Kimball said. “You obviously can’t go back, but you can’t help but long for those days. The reason is simple: it was fun. There were definitely struggles, but when you boil it down, why did they do it for so long, and why are they still coaching? Because it’s fun.”

Former ASU linebacker and now Higley coach Eddy Zubey agreed, adding: “For me, it’s the physical aspect of the game. Just being able to hit people – that’s not allowed in society.”

After Plummer entered the 1997 NFL Draft, Campbell, a junior at the time, and redshirt freshman Ryan Kealy were in a battle for the starting job at quarterback during fall camp.

Campbell lost that competition and regrets putting too much pressure on himself, which he believes sealed his fate as a backup for most of his ASU career.

And while he left the game on his own terms, which included starting and leading the Sun Devils to a win on New Year’s Eve in the 1997 Norwest Sun Bowl, regrets still creep into his mind almost three decades later.

That isn’t surprising to Kimball, the psychology professor.

“One of the reasons why there is that regret is just facing the reality that you can’t go backwards,” Kimball said. “It’s just missing the experience, and it’s just hard to come to that realization that – no matter how hard you wish – it’s not going to happen.”

Whether it’s Roque, whose career was cut short due to injury, Plummer, who chose to retire during his prime for a simpler life, or former ASU safety Adam Archuleta, now a national broadcaster, it’s impossible to expect any player to have a finite answer on how to navigate life after their last snap.

Everyone’s experience, background and circumstances are different.

But if Roque and Campbell could leave every athlete with one piece of advice, Roque said his would be that sports “is only five seconds of your life.”

And Campbell said, “Whether you had dark days or not, the dark days are just dark days. They weren’t a dark life.”

Zubey added, “You need to find something that you love to do. Whether it’s being part of a team, a leader of the team, or a cog in the wheel, you just have to find your niche. Go work for a company and go be the best employee. Go start your own business and be the best CEO you can be. In your work life, mirror that same mentality you had as a football player.”

For more stories from Cronkite News, visit cronkitenews.azpbs.org.