- Slug: BC-CNS-Race Dominican,2490 words.

- 9 photos available (thumbnails, captions below).

By Morgan Casey

Cronkite Borderlands Initiative

SANTO DOMINGO, Dominican Republic – The Dominican Republic is cracking down on migration from Haiti, in an effort that is roiling the country and leading to accusations of racism in the Dominican government and society.

Under the assumption that black skin and curly hair equals Haitian, Black Dominicans are being targeted by police, the military and, sometimes, their fellow citizens.

The discrimination against Black Dominicans was so severe that the U.S. Embassy in the country issued an advisory last November to “darker skinned U.S. citizens and U.S. citizens of African descent” traveling to the country. The advisory said the Dominican government was detaining dark-skinned travelers, assuming they could be Haitian.

The Dominican government refuted the discrimination claims, saying it was “manifestly unfounded, untimely, and unhappy.”

Leonel Fernández, who served three terms as the Dominican president, also denied charges of racism in the country.

“What we’re dealing with here is a historical issue, a geographic issue, a migratory issue of survival between Haiti and the Dominican Republic, but it’s not a racial issue,” Fernandez told Dominican Today in November 2022.

But racial discrimination in the Dominican Republic and the governmental denial of its existence is nothing new according to AfroDominican activists; it is why their movement exists. The activists’ methods vary widely, from anti-colonial tours to grassroots education, but their goal is the same: equal rights for Black Dominicans.

Struggling to embrace a Black identity

One of the largest AfroDominican organizations is Reconoci.do. The group fights for the rights of Dominicans of Haitian descent and against discriminatory policies and culture.

A large part of Felipe Fontes’ work as coordinator for Reconoci.do is deconstructing Black Dominicans’ self-discriminating views, which he said were built by centuries of anti-Haitian and anti-African rhetoric.

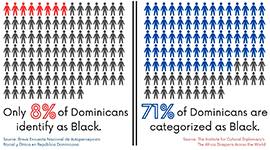

Many Dominicans refuse to identify as Black. Only 8% of Dominicans identify as Black in some capacity, according to a 2022 study of the Dominican Republic by the United Nations. It’s no wonder they don’t: Black Dominicans face difficulty obtaining official documents, accessing education and other discrimination.

“All our institutions are telling you not to be Black,” Fontes said.

Non-Dominicans more readily identify many Dominicans as Black. The country has the fifth-largest portion in the world of the African diaspora, with almost 8 million Black people living in the country, according to the Institute for Cultural Diplomacy. If the ICD’s estimate is correct, that would mean just over 70% of the country’s 11.3 million residents have African roots. Those numbers offer a huge contrast with the U.N. study of Dominicans’ self-reported racial identity that put the number of Black Dominicans at 896,000, about 7 million fewer than the ICD report.

The U.N. survey found many categories for self-identification within the Dominican population, including, translated from Spanish, “Black,” “mulatto”, “brown,” “Indian” and “white.” Within each of these were sub-categories: “oscuro” or “dark,” and Spanish variations on “light,” including “claro” and “lavaito,” terms the survey authors said were used to “distance” a person from “Blackness.”

“The Dominican Republic is a country primarily made up of Black people that don’t identify as Black,” said Fontes. “They identify as Indio and white because of poor education.”

Reconoci.do puts on seminars and community events to provide the Black history education, which is lacking in the official Dominican history curriculum. The purpose: To get Dominicans of Haitian descent to change their psyche, forgoing ideas of “negro malo” and instead learning that Black is beautiful and to be proud of their Black identity.

Once Reconoci.do teaches a person to view Blackness positively, they encourage that person to become a community ambassador and help others unlearn anti-Black ideas.

Reconoci.do is also petitioning the Dominican government to change its history curriculum. Fontes said Reconoci.do’s wants to remove the fallacy that Haiti and Black Dominicans are the enemies popularized by Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo, who ruled the country from 1930 until his assassination in 1961.

However, Reconoci.do says it is making little progress in changing people’s discriminatory thinking and even less with the Dominican government.

“The psychological and social consciousness of the Dominican Republic isn’t changing easily,” said Fontes.

The Dominican Republic’s history of anti-Blackness

The Dominican Republic has a long history of anti-Blackness, according to Saudi Garcia, an assistant professor of anthropology at the New School and executive director of In Cultured Company — a U.S.-based activist organization focused on correcting the history of Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Garcia said much of the Dominican Republic’s anti-Blackness stems from Trujillo’s 30-year reign.

Trujillo spent much of his dictatorship distinguishing the Dominican Republic from Haiti, with a push from the United States to do so. Since he couldn’t do it at first economically, as both countries had relatively similar economies, he did it racially.

“(The Trujillo) dictatorship was interested in presenting the Dominican Republic as a more white nation in comparison to Haiti,” said Garcia.

Trujillo embedded prejudices against anything with an African, not just Haitian, origin, Garcia said.

That prejudice still exists in Dominican society today and forms the basis of the country’s migration and citizenship policies, Dominican anthropologist Tahira Vargas told Dominican Today in September 2022.

The Dominican Republic has three primary laws governing migration and citizenship.

The first, Law 285-04, was passed in 2004 and classified recently migrated Haitians and those settled in the country as “nonresidents” and perpetually in transit.

In 2013, the Dominican government edited its constitution with Judgment 168-13, more commonly known as La Sentencia. La Sentencia retroactively eliminated birthright citizenship for Dominicans born between 1929 and 2010 to foreign-born parents, most of whom were Dominicans of Haitian descent.

Finally, last November, the government passed Decree 668-22, creating a specialized police unit to prosecute anyone unlawfully occupying private or state-owned property. The force primarily targets bateyes, which are settlements mostly occupied by Haitian workers near sugar cane fields.

The laws built off each other, explained Wendy Hunter, professor of government at the University of Texas at Austin. Each law grew the maze of bureaucracy to prevent Dominicans of Haitian descent and Haitian migrants from ever gaining Dominican citizenship, she said.

The laws have increased discrimination, according to Fontes.

“Racism has grown, particularly in the last 10 years,” Fontes said.

Liliana Dolis, general coordinator of the Movimiento de Mujeres Dominico-Haitianas, the Dominican-Haitians Women’s Movement, said the country’s border patrol is highly discriminatory. People with dark skin and/or non-Hispanic surnames face persecution by the border patrol because they are presumed to be Haitian.

“Dominicans of any origin have been arrested because of their skin color,” Dolis said.

Because of this history, the Dominicans whose skin color is too dark to allow them to identify as white identify as the next best option in the racial hierarchy: Indio. Around 45% of Dominicans identify as Indio, according to the U.N. study.

Creating a Black consciousness

With a small percentage of Dominicans identifying as Black and even fewer embracing their African heritage, Danilo Contreras, an assistant professor of political science at Wellesley College, said it is almost impossible to form a collective.

“The kind of Blackness that you see in the DR, it’s not the kind of Black group identity that most Black Americans in the U.S. identify with,” said Contreras. “You don’t have a politicized Black group consciousness for a number of historical and institutional reasons.”

AfroDominican activists are trying to cultivate that Black political consciousness in the Dominican Republic.

“It is not enough to accept that this (discrimination) is going to happen,” Dolis said. “I have to keep going. Despite everything, I have to fight to make a change possible.”

One method for jump-starting political activism includes bringing issues of anti-Blackness and racial discrimination into other causes. For example, the co-founder of Reconoci.do, Elena Lorac, spoke at a protest for abortion and women’s rights in March about the discrimination faced by Black Dominican women.

Other tactics are Reconoci.do’s grassroots education model. MUDHA, Dolis’ Dominican Haitian women’s group, also uses this model to get the members of the 20 bateyes they operate in, most of whom are Dominicans of Haitian descent, to proudly claim their Haitian identity.

MUDHA also teaches people how to advocate for themselves and their community.

“We empower the community so that they can claim and demand what their rights are, that they are trained and prepared to speak to local authorities to solve their problems,” Dolis said.

However, the Dominican Republic’s long-standing discrimination against Black Dominicans makes it hard for them to obtain enough political power to advocate for themselves, said Fontes.

“We do not have access to more than very little. That limits you in everything because it is a chain,” Fontes said. “If you are in power, you drag your group to power. And we have 300 years, 400 years of being far from power. Therefore, we are limited in everything.”

Rewriting Dominican history

In Santo Domingo, Ruth Pion recounts Dominican history in ways that acknowledge the country’s enslavement of Africans and its connection to discrimination against Black Dominicans today.

Pion founded AfrohistoriaRD, a tour company that operates in the colonial district and educates people about the Dominican Republic’s mostly untold Black history. Her tour, Hidden History: A Decolonial Tour, retells the history of the Dominican Republic with a focus on its roots in slavery.

“Afrohistoria is a disruption of (the Dominican Republic’s Spanish) narrative. It’s asking people to ask themselves, ‘Is this true?’, to challenge people to read the history books again, or to look for other sources, to hear other voices studying our history,” Pion said.

Pion says she is the only tour guide who discusses slavery in the Dominican Republic. The union of colonial district tourism guides dictates the scripts of other colonial district tours and doesn’t mention slavery or any African contributions to Dominican culture.

On Pion’s tour, people go to the tops of the walls surrounding Alcazar de Colon – the fortress of Columbus – walking the same worn and uneven stones thousands of enslaved Africans were forced to walk, and they see the Puerta de las Atarazanas, the port entrance to the colonial city, called the Gates of No Return.

The Dominican Republic’s lack of Black Dominican history education is purposeful, Pion said.

“If we’re not communicating Black history through archaeological sites, through tourism, through education, through museography, then there must be a political intention,” Pion said.

The political intention is to maintain the juxtaposition of the Dominican Republic as a white country and Haiti as a Black country, Pion said.

That’s why the colonial district’s walls and the Gates of No Return are crumbling, despite the colonial city’s designation as a UNESCO heritage site. Without physical reminders of slavery, Pion said the country wipes clean its connections to Africa.

To wipe clean the country’s history, the government actively destroys some physical reminders of slavery. La Picota, a column where enslaved Africans would be tied up and flogged, no longer exists. The government destroyed it in 1864 and replaced it with a statue of Christopher Columbus and the last Taíno queen, Anacaona, who fought against the Spanish.

“They delete the evidence of colonial violence,” Pion said.

Other physical reminders are destroyed through a lack of preservation by the government. La Negreta, a warehouse complex that housed enslaved Africans before their sale, collapsed years ago and is now mostly rubble.

Predominantly Black towns like Santa Barbara are also left to sink into poverty and crime, said Pion. Santa Barbara was one of the first Black towns in the Americas and where La Negreta formerly sat.

Pion hopes learning about Black Dominican history and the history of slavery in the country, even without the physical monument to it, will advance the AfroDominican movement.

“If we can see a historical starting point, maybe we can see an end,” Pion said.

Hair salons, a place of resistance

Located off Expreso 27 de Febrero in Santo Domingo, Grecy’s Natural Hair is a salon that caters to natural hair.

Salons like Grecy’s are few and far between in the Dominican Republic. Most salons specialize in straightening hair, either with heat or chemicals. Dominican salons are known for how straight they can get even the curliest hair textures. The salon’s treatments are so effective, they were popularized in the United States under the name Dominican Blowout.

Women with even the slightest curl to their hair are often discriminated against. They can be passed over for scholarships, as was the case for Nicky González Méndez, a Dominican political science student who said she didn’t receive a scholarship from the Ministry of Education in 2016 because of her hair. They also can be sent home from school, which is what happened to 11-year-old student Omara Mia Bell Marte in 2019 for wearing her natural hair.

“Hair surpasses skin color as the most salient racial determinant,” wrote Jacqueline Lyon, an assistant professor of anthropology at Bates College, in her paper, Pajón power.

Women with natural hair are fighting against this discrimination and Dominican beauty standards simply by existing, said Katherine Aleantoa, the manager of Grecy’s Natural Hair. She hopes that, as more women keep their natural hair, they can make society realize that natural hair isn’t any different from other textures.

“I don’t want (wearing your natural hair) to be an act of resistance,” Aleantoa said. “I don’t want it to be a movement, I want it to be something natural.”

Aleantoa and Pion said the natural hair community in the Dominican Republic is growing. Aleantoa sees the women bringing their friends into the salon, having convinced them to start on their natural hair journey.

“I just want to motivate people to build self-love,” Aleantoa said.

The long road ahead

While the AfroDominican movement has made inroads in convincing women to wear their natural hair, learn Black history and embrace their Black identity, Contreras, the Wellesley College professor, believes much work is still needed.

“The challenge is whether the movement can also have a similar effect in the electoral space where they can parlay the kind of social influence that they’ve had,” Contreras said.

AfroDominican activists recognize the difficulty of unraveling centuries of anti-Blackness from Dominican society. One of their biggest obstacles is people’s wariness of associating with the AfroDominican movement for fear of being attacked.

“People who are Black cultural workers or artists, people who are challenging the European, Hispanic-centered narrative are literally being physically attacked by authoritarian fascist groups, which are growing in the Dominican Republic over the past five years,” said Garcia, the New School professor.

Hunter, the University of Texas professor, pointed to one ray of hope for AfroDominican activists: U.S. President Joe Biden’s halting of imports from Dominican sugar company Central Romana Corp. for human rights violations.

“I think if progress is going to be made, it’s not going to be for humanitarian reasons,” said Hunter. “I think it’s going to have to come from trade issues.”

International attention is what the AfroDominican movement needs, said Fontes.

“It forces people to change,” said Fontes. “The government pays more attention to us if there’s international attention pressuring them to do so.”

For more stories from Cronkite News, visit cronkitenews.azpbs.org.

^__=

Reconoci.do coordinator and co-founder Elena Lorac speaks about racial discrimination at a “3 Causales” march in Parque Independencia on March 4, 2023. (Photo by Morgan Casey/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

Few Dominicans identify as Black despite outside organizations classifying many of them as such. (Graphic by Morgan Casey/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

Calle General Cabral divides the colonial district and Santa Barbara, one of the first free Black towns in the Americas. Santa Barabara is characterized by poverty and violence despite its proximity to the colonial district. (Photo by Morgan Casey/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

Women with natural hair often face discrimination, causing many to avoid natural hair salons like Grecy’s Natural Hair. They opt for straightening their hair instead. (Photo by Morgan Casey/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

Ruth Pion, the founder of the AfrohistoriaRD tour, listens to a tourist speak about their experiences with racism in the Caribbean on a March tour around the colonial district. (Photo by Morgan Casey/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

The walls around Alcazar Colon and the Puerta de las Atarazanas, dubbed the Gates of No Return by AfrohistoriaRD founder Ruth Pion, have no plaques or markers memorializing the thousands of enslaved Africans that walked across them. (Photos by Morgan Casey/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

At the feet of the Christopher Columbus statue in Parque Colon, a statue of the last Taíno queen Anacoana sits, writing in latin: “Great and illustrious Columbus.” (Photo by Morgan Casey/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

Grecy’s Natural Hair manager Katherine Aleantoa wants to teach more women self-love when they speak about their natural hair. (Photo by Morgan Casey/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

The walls around Alcazar Colon and the Puerta de las Atarazanas, dubbed the Gates of No Return by AfrohistoriaRD founder Ruth Pion, have no plaques or markers memorializing the thousands of enslaved Africans that walked across them. (Photos by Morgan Casey/Cronkite Borderlands Project)