- Slug: News21-After Roe-Abortion Pill Networks (Abridged),1400 words.

- A full-length version of 2,270 words is also available.

- 6 photos, video story available (thumbnails and captions below).

By Marien López-Medina, Kevin Palomino, April Pierdant and Tori Gantz

News21

MONTERREY, Mexico – Verónica Cruz Sánchez watched something remarkable happen from the office of her women’s rights organization in Guanajuato, the capital city of one of this country’s most conservative Catholic states.

Founder of Las Libres – “the free” in English – she had built an underground abortion-pill network in a country where having the procedure could have meant going to jail.

In September 2021, the Mexican Supreme Court issued a surprise ruling that abortion was no longer a crime – not even in places like Guanajuato, where it continues to be outlawed by the state.

That same month across the border in the U.S., Texas instituted a so-called “fetal heartbeat bill” that effectively outlawed abortion.

And the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization case was before the U.S. Supreme Court, with the potential to reverse Roe v. Wade and end almost 50 years of abortion rights in America.

“It was crazy,” Cruz Sánchez said. “For those of us working in abortion, the example to follow was the United States. All the countries in Latin America wanted a Roe … we wanted to have the constitutional right.”

Suddenly it was Mexico at the vanguard of abortion access, and activists knew they could help the U.S.

“We could give them all the support and training,” Cruz Sánchez said. “How do you find the medication? … How do you do the logistics so the pills get into the hands that need them? How do you guarantee security for everyone?”

She reached out to other groups that distributed abortion medication in Mexico, as well as abortion rights organizations in the United States, and started to build the “red transfronteriza” – the cross-border network.

And she had a specific U.S. population in mind.

“We knew there was a large proportion of undocumented Hispanic immigrant women from Central America who cross through Mexico all the time,” Cruz Sánchez said. “And that was one of our motivations for why we wanted to support Texas – not only for all women but especially for undocumented immigrant women.”

Networks of pills

In a residential neighborhood with a full view of the Cerro de la Silla, Monterrey’s iconic mountain peak, Vanessa Jiménez runs Necesito Abortar out of her spouse’s family home.

There, she stuffs manila envelopes to create at-home abortion kits for delivery. Each includes small bags containing a single mifepristone, four misoprostol pills, two ibuprofens and four sanitary napkins.

In the U.S., the Food and Drug Administration has approved a regimen of mifepristone and misoprostol to terminate pregnancies up to 10 weeks and says it is both safe and effective.

Jiménez has an informal network of family and friends who take these kits and vials of pills into the United States during visits over the border.

Once the pills arrive, Jiménez accompanies patients through the abortion process by phone.

There’s nothing illegal about carrying medication over the border; Americans cross into Mexican border towns all the time to buy drugs that would otherwise require a prescription in the U.S.

But giving pills to someone in Texas to end a pregnancy could land you in jail.

“Someone could be charged with a crime in Texas for providing those abortion pills to someone else in Texas to self-manage their abortion,” said Blake Rocap, legislative counsel for Avow, an abortion advocacy group based in Austin, Texas.

Despite this, volunteers have stepped up to work with the cross-border network as “acompañantes,” people who not only provide abortion medication but stay through the process by telephone, using guidelines from the World Health Organization.

“We had to explain things. … What is misoprostol? What does it do? Can you detect it in the body? How does it function?” Jiménez said. “In the end, I believe, the purpose was not to solve the problem in the United States but rather to share the experience that we have so that there, in their own context, they can form the networks that exist here.’’

News21 interviewed a Mexican woman who volunteers as an “acompañante,” carrying pills into the U.S. She gets her supply from Las Libres, and pregnant people in the U.S. reach her via social media.

“I do it out of passion,” she said, “with the conviction that I’m not doing anything wrong. The laws are what need to change.”

One recent weekend, she drove to El Paso, Texas, to drop medication with her U.S. distributor.

The distributor gets two to three requests a month for pills in states like Texas, Kansas and Arizona. She mails the pills using the U.S. Postal Service, because private carriers require personal information.

“I am not the only one,” said the distributor, who along with the acompañante requested anonymity out of fear of legal repercussions in Texas.

Since its birth last year, the cross-border network has earned significant news coverage in U.S. media outlets, and with it, more clients. Post-Roe, Las Libres has seen requests for abortion pills from the U.S. explode – from 10 a day to 300 in some instances, Cruz Sánchez said.

But the network has fallen short in one area.

“Everyone thought that since we were a Spanish-speaking organization in Mexico, most of the people in the United States who were going to look for us would be Spanish-speaking, undocumented immigrants,” Cruz Sánchez said, adding: “The majority only speak English.”

Cut off from care

People living in the country illegally have always been cut off from health care services because of poverty, language barriers and fear. They are ineligible for federal health care programs and are often hesitant to sign up for state benefits or seek health care because of concerns over deportation.

Cathy Torres, with the Frontera Fund abortion fund, works in Texas’ Rio Grande Valley, where at least 10 percent of 1.4 million people are in the country illegally. She paid for people to travel out of state to get abortions after Texas’ fetal heartbeat law took effect. But with the reversal of Roe v. Wade, she had to stop funding travel. She fears civil or criminal liability.

She said immigrants living in the Valley illegally are “landlocked.” Even if they travel for services, they must pass through Customs and Border Protection checkpoints.

“So they’re having to grapple with, ‘God, I either really, really risk it’ or ‘I just stay pregnant,’” Torres said.

The obvious option for people who can’t travel is self-managed abortion at home.

As of 2020, medication was used in more than half of abortions in the U.S., according to the Guttmacher Institute, an abortion-rights organization. But with restrictive abortion laws, 14 states now outlaw taking medication to end a pregnancy, according to the health policy group KFF.

“People are taking their health into their own hands,” said Texas Civil Rights Project President Rochelle Garza. “Self-managed abortion is something that is rising as a response to the lack of health care.”

The cross-border network works in the Rio Grande Valley. Couriers from Jiménez’s Necesito Abortar in Monterrey cross into McAllen, one of the main cities.

But ask anyone on the U.S. side about the network, and they go silent.

“It’s this confusion of what is legal,” said Nancy Cárdenas Peña, campaign director for Abortion on Our Own Terms, which advocates for self-managed abortion through medication.

In one case, a Rio Grande Valley woman was arrested for murder over an alleged self-induced abortion. After protests by activists, the charges were dropped.

New efforts

Cruz Sánchez is thinking of new ways to reach people who might need the services of Las Libres or the cross-border network, like asking Texas-based volunteers to place stickers with Las Libres’ social media accounts in bathrooms, bars, restaurants, parks and other public spaces.

But the effort is slow-going.

“In terms of abortion, Texas has a lot of complexities. The people there are paralyzed right now by the legal situation,” Cruz Sánchez said.

In the end, it requires going door to door, person to person, like the organization did in Mexico, and getting people in the U.S. to organize and form their own networks.

“If Mexico could organize without a single peso, just by organizing the people, obviously the U.S., with more money, can do it,” she said. “But the big question is: Who’s going to do the groundwork?”

This report is part of “America After Roe,” an examination of the impact of the reversal of Roe v. Wade on health care, culture, policy and people, produced by Carnegie-Knight News21. For more stories, visit https://americaafterroe.news21.com/.

For more stories from Cronkite News, visit cronkitenews.azpbs.org.

^__=

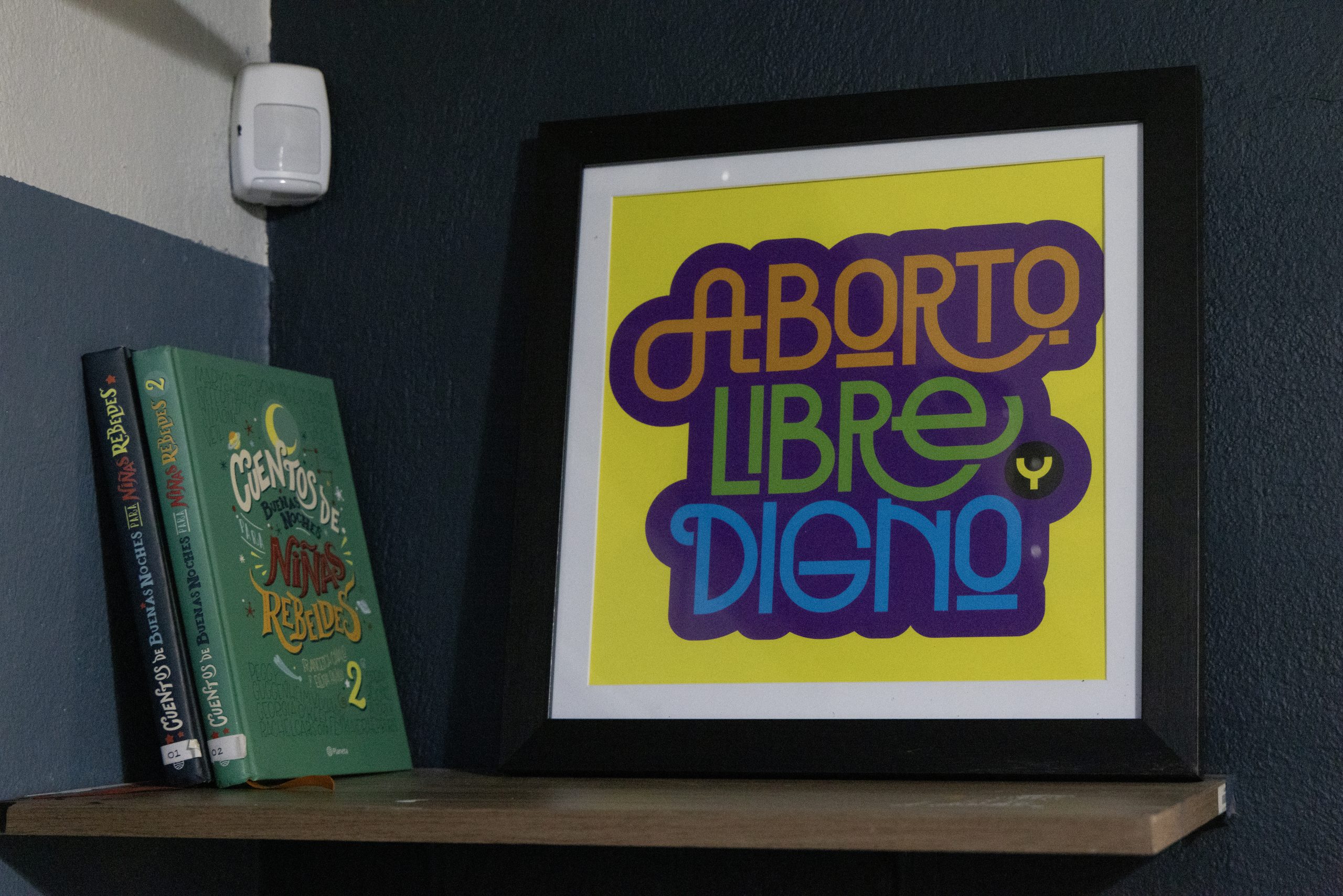

A picture reads “Abortion: Free and Dignified” at Necesito Abortar in Monterrey, Mexico. (Photo by April Pierdant/News21

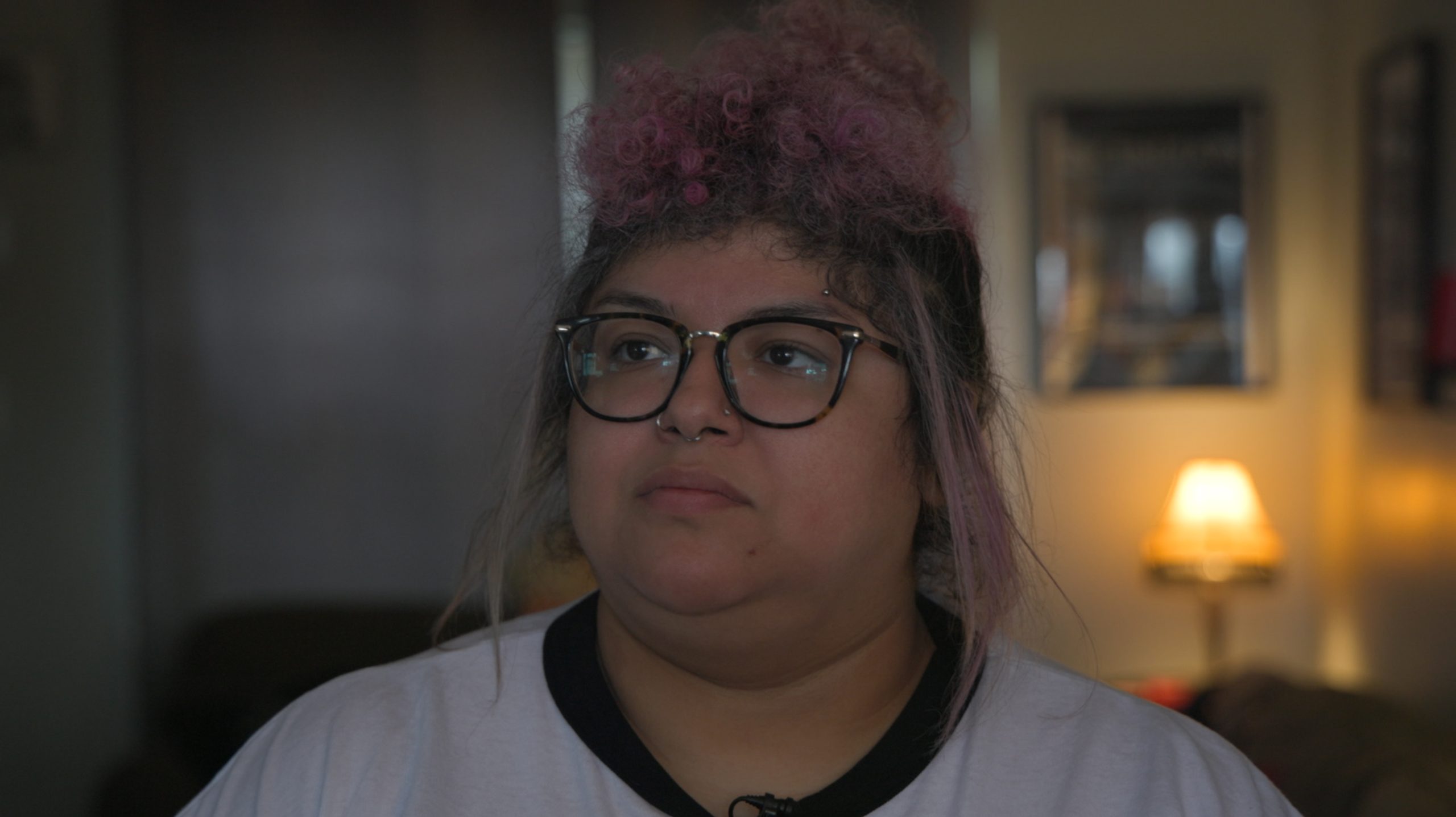

Cathy Torres, based in Texas’ Rio Grande Valley, is the organizing manager for Frontera Fund, which pays abortion costs for Texas residents. (Photo by Kevin Palomino/News21)

Cathy Torres, organizing manager of Frontera Fund in Texas’ Rio Grande Valley, said the demand for travel abortions in the region went from eight a year to 15 a month after the state’s six-week abortion ban took effect. The closest access state, New Mexico, is a 12-hour drive, and she was flying people as far as Las Vegas and Virginia. (Photo by Kevin Palomino/News21)

Nancy Cárdenas Peña is an advocate for reproductive justice and self-managed abortion in Texas’ Rio Grande Valley. (Photo by Kevin Palomino/News21)

Rochelle Garza is an attorney in Brownsville, Texas, fighting for immigrant civil rights, including access to abortion services. (Photo by Kevin Palomino/News21)

Vanessa Jiménez runs an abortion pill network called Necesito Abortar from her home in Monterrey, Mexico. Jiménez has an informal network of family and friends who take pills into the United States during visits over the border. (Photo by April Pierdant/News21)