- Slug: Sports-9/11 Sport Impact, 1,700 words

- Photo available

By Abby Sharpe and Erin Slinde

Cronkite News

PHOENIX – Thunderstorms hit New York City on Sept. 10, 2001. The gray skies foreshadowed the dark, painful days ahead.

Tuesday morning, Sept. 11, 2001, was different. The sun was shining, the sky a perfect blue. New Yorkers headed to work. Thousands took an elevator to one of the 110 floors of the Twin Towers at the World Trade Center in lower Manhattan.

Others boarded flights, like American Airlines Flight 11, United Airlines Flight 93, United Airlines Flight 175 and American Airlines Flight 77. The planes never reached their intended destinations.

The sports world immediately felt the impact of the Twin Towers falling, as did the rest of the country. Seasons halted, with players, coaches and executives unsure of when it would be appropriate to resume games, as the wound of a domestic terrorist attack sat open and bleeding.

Everybody has a story from that fateful day. Here are three from sports figures close to the pain of Sept. 11.

The coach

Arizona State football coach Herm Edwards was a first-year head coach of the New York Jets at the time of the attacks. Edwards’ team wrapped up the first week of the season Sept. 9 with a loss against the Indianapolis Colts at Giants Stadium in New Jersey.

The players were off the following two days, but Edwards was watching film at the Jets’ practice facility at Hofstra University to prepare for the next game against the Oakland Raiders. He looked out the window to the practice field.

“It was a clear day,” Edwards said. “LaGuardia Airport is not that far away. I’m looking out a little bit. It’s a nice, clear day, but I don’t see any airplanes. It’s strange to me.”

Another hour went by, and Edwards still didn’t see a plane flying by. That’s when he decided to turn on the television.

“All of a sudden, I see towers. I see a plane on the news running into the tower,” Edwards said. “We have been under attack.”

Edwards and the coaching staff walked down to the general manager’s office. Information came in bits and pieces, everyone attempting to figure out what happened. Then another realization hit: The Jets had a game scheduled that weekend.

“I look at the GM and go, ‘Wow, I hope we’re not playing a football game this week,’” said Edwards.

NFL headquarters, located in the heart of New York City, didn’t know the answer to that yet. Like everyone else, the commissioner’s office was trying to process the events of Tuesday morning.

The players began to trickle in. Edwards didn’t feel it was appropriate to play that week, but he gathered the team and headed out to practice.

“We go out, and 20 minutes into practice, and there’s no life at all,” Edwards said. “So I said, ‘Guys, come on, let’s go.’”

Back in the meeting room, Edwards let the players decide if they wanted to play the Raiders or forfeit.

The team voted to not play, days before the NFL elected to cancel all games that week. Instead, the team gathered together and took four buses to the place where the Twin Towers once proudly stood over New York City.

“We loaded trucks that would go in and bring in water and supplies to all the first responders,” Edwards said. “We came down there and I said (to the first responders), ‘You’re truly the heroes.’”

Sunday, Sept. 23 rolled around. Almost two weeks after the towers fell, the Jets traveled to Foxborough, Mass., to play the New England Patriots.

“I can remember walking into that stadium and talking to coach (Bill) Belichick, and the red, white and blue, and all the flags, and the emotion of the crowd,” Edwards said. “We all felt for those that lost their lives and the ones who lost their lives going into those buildings.

“Once the game kicked off, and the guys ran out there with the flags, it was an emotional deal.”

Edwards and Belichick agreed before the game that they didn’t know how the teams were going to play. But 108 players suited up in front of a nearly sold out crowd at Foxboro Stadium, illustrating the power sports have to heal and unite people across the country.

The player

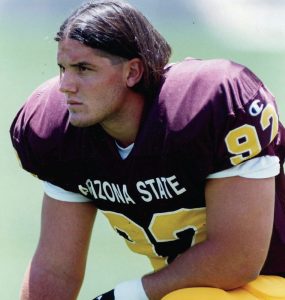

Jeremy Staat joined the ASU football team in 1996 as a junior college transfer from Bakersfield, Calif. At ASU, Staat won the Morris Trophy and played in the Sun Devils’ lone trip to the Rose Bowl. The Pittsburgh Steelers selected the defensive end 41st overall in the 1998 draft.

In 2001, Staat was home in Scottsdale, deciding what to do after getting cut by the Steelers. He got a call from a friend, asking if Staat was watching the news.

Staat told him no. The friend shared the news with Staat.

“He said, ‘Well, we’re under attack,’” Staat said. “I just remember turning on the TV, and going, ‘What the hell is going on?’ This is America, we don’t get attacked here.”

While playing for the Sun Devils, Staat befriended linebacker Pat Tillman. In 2001, Tillman was playing for the Arizona Cardinals. Staat said the two talked after the attacks of Sept. 11.

“Once 9/11 happened, we had some pretty in-depth conversations that changed the trajectory of our lives,” Staat said. “That was a defining moment in our life. I think that’s where we stopped believing in the hype of the NFL. Service over self is what we need to do.”

The attacks spurred Tillman’s enlistment in the Army in May 2002. Tillman talked Staat out of enlisting at the same time — Staat needed only three more games in the NFL to be eligible for the league’s retirement benefits.

Tillman deployed to Iraq in 2003, followed by a tour in Afghanistan in 2004.

On April 22, 2004, Tillman was killed by friendly fire in eastern Afghanistan.

The loss took a toll on Staat, who joined the St. Louis Rams for a couple games in 2003. With his NFL career over and his friend killed, Staat struggled with what to do next.

He decided to follow his father and grandfather and enlist in the military. Staat served in the Marines from 2005 to 2009, and deployed to Iraq in 2007.

There’s one thing Staat knows that Tillman would want to share with others, 20 years after the terrorist attack that changed the course of numerous American lives, including those of Staat and Tillman.

“He would want us to remember the victims of 9/11. He wouldn’t want it to be about Pat or Jeremy Staat, or anybody else,” Staat said. “We both wanted the world to remember the victims and what we can learn from (that day).”

The journalist

In early Sept. 2001, Diane Pucin, a sports reporter for the Los Angeles Times, left the newsroom and headed to the east coast for multiple events — Penn State’s first football game of the season in State College, and the U.S. Open in Queens, New York.

It was late on Sunday, Sept. 9. The Nittany Lions lost to the University of Miami eight days earlier. Lleyton Hewitt and Venus Williams captured the men’s and women’s titles, respectively, at the Billie Jean King National Tennis Center — 15 miles away from the place where chaos and tragedy would ensue two days later.

Pucin’s editor asked her to delay her flight out of Logan International Airport in Boston until Tuesday. Only two flights remained: one departed at 8 a.m., the other at 3 p.m.

Initially, Pucin booked the 8 a.m. flight, but changed to the 3 p.m. flight after realizing how exhausted she would be following the U.S. Open. She planned to fly from an airport in Islip on Long Island to Boston’s Logan. Tuesday morning rolled around and, about the time the morning flight would’ve left Boston for Los Angeles, Pucin got a call from her husband.

From the TV in her hotel room at the Grand Hyatt in Manhattan, Pucin watched American Airlines Flight 11 crash into the north tower of the World Trade Center.

Quickly, Pucin realized Flight 11 was the flight she almost took back to Los Angeles.

The phone lines were jammed. Pucin couldn’t get a hold of anyone from her office, so she went to the lobby.

On any normal day in New York, cabs crowd the street. That Tuesday, only one was near the hotel.

Pucin asked the cab driver to drive her as close to the scene as possible. She paid $300 for that ride.

During the 10-block drive to the burning World Trade Center, she saw people covered in dirt and ash, while others wrote down details of missing loved ones and posted flyers to walls nearby.

She ended up at Bellevue Hospital, a 15-minute drive from what is now known as Ground Zero, trying to interview people who were standing outside of the hospital, wondering if their loved ones were dead or alive.

Pucin stood there for three or four hours as only a few patients were brought in to the hospital. That’s when she came to her own conclusion.

“That day you were either completely fine or you were dead,” Pucin said.

There were no flights and no rental cars available in the days following the terrorist attack. Pucin was stranded in New York City until Saturday, when she finally got a flight out of Philadelphia.

As she drove over the East River, Pucin saw the aftermath of the two towers, now replaced by two clouds of black smoke.

“Those two towers were so familiar,” Pucin said. “To see the two plumes of smoke and the smell, it will never leave you.”

Pucin flew back to Los Angeles. She said she couldn’t stop watching the TV coverage.

“I watched every single bit of it and it makes me weep every time,” Pucin said. “I know what happened. I know how it turned out.”

Slowly but surely, sports came back, but the event still had a great impact on her and made her remember that horrible day.

“It has stuck with me forever in a way that I can’t describe,” Pucin said. “It just made you think to yourself, ‘Why were those people killed and I wasn’t?’ It just didn’t seem fair somehow.”

For more stories from Cronkite News, visit cronkitenews.azpbs.org.