- Slug: Sports-Inside CFP Selection, about 1,500 words.

- Photos available

By Erica Block

Cronkite News

GRAPEVINE, Texas – I knew that participating in a mock College Football Playoff (CFP) selection would be a worthwhile learning experience. I didn’t expect to leave the Gaylord Texan Resort with the impression that the CFP selection committee may be the most democratic governing body in sports.

Last week, that evenhandedness was apparent when I traveled to Grapevine, Texas, for a firsthand look at the process. From the setting to the snacks provided, the mock selection emulated the real thing, down to the smallest detail.

The College Football Playoff selection committee is a diverse mix of athletic directors, journalists, a professor, former players and retired coaches. To give students an inside look at how the selection takes place, the committee hosts mock events to illuminate the nuance and rigor involved in the process of ranking teams.

A dozen other sports journalism students and I deliberated over team rankings, just as the actual committee members would. All of us sat at the same table and used the same CFP-branded laptops that the actual committee members use. We had access to the same analytics. And we ate bacon at breakfast, like the real committee, before getting down to business.

The CFP committee has a number of amusing customs. Eating bacon is just one of them.

Another tradition requires each committee member to “hang his or her hat at the door,” CFP Executive Director Bill Hancock said.

The caps symbolize the idea that when the committee members enter that room, they remove their alumna or alumnus hats, any affiliation with that school, or any loyalties toward a specific team.

While the gesture reinforces the impartiality of the committee, Hancock was also speaking literally. There is a hand-crafted mahogany hat rack beside the conference room door where the deliberation takes place. Its pegs are fashioned in the shape of footballs. Thirteen plain white Nike baseball caps bearing no logo or insignia dangled from the pegs. An ironing board stood in the corner of the conference room to remind me that my job was to “iron out” the details,” as Hancock explained.

I left my biases at the door.

For the next four hours, there was no such person as Erica Block. I had transformed into CFP committee member Paola Boivin, who also directs the Cronkite News Sports Bureau here in Phoenix.

People say it’s cool to be your own boss. Pretending to be your grad school professor probably isn’t what they meant, but whatever. I was determined to do justice to my news director.

Seated at a long table, each student represented a member of the committee and sat in that member’s seat. Screens displaying statistics and win-loss record comparisons surrounded us. Sitting at one end of the table, Hancock distributed copies of the College Football Playoff Selection Committee Protocol to each committee member. “You people will complete in about four hours what it takes the committee about 16 hours to accomplish,” Hancock said. “Just the tip of the iceberg. It’ll be fun. You’ll see!”

Hancock has an enthusiastic and cheery disposition, but it’s also clear that he takes this task seriously. Before long, I realized I would be abstaining from any discussion involving Arizona State, or debate over which teams to pick as ASU’s opponents. I didn’t have to leave the room, but the real recused committee members do.

If a committee member has any connection to a team, he or she must exit the room when that team is discussed and refrain from voting in that round. Not only does this policy function as a check against committee members’ personal biases, but it eliminates any pressure that could be exerted on committee members to vote for a school from which they receive their paycheck.

“They get to wait outside the room,” Hancock said. “We like to say they get to snack on the leftover bacon.”

Recused committee members can answer factual questions, such as whether a team’s star quarterback was injured and sat out of a game where there was an unexpectedly lopsided score. As Paola, I had to follow the CFP recusal process during several rounds of the ranking process. Not only was I blocked from voting in rounds involving Arizona State, but I couldn’t rank teams that would affect which team Arizona State might face in the playoffs.

The mock selection always uses real statistics from a previous year so that the participants can examine a full season of data. We used the 2014 college football season as the basis for our mock selection. It was a year in which ranking difficulties hinged on a lack of head-to-head matchups among the strongest teams, as well as a varied range of teams’ strength of schedule.

The selection process began with each committee member recording their 30 best teams on their own CFP-branded laptop. Florida State, Oregon, Ohio State and Alabama were my four teams.

The other students and I repeated the process over and over again, evaluating bands of three to six teams at a time. We settled on our top six picks, then selected which teams would fill the No. 7 through No. 10 seeds, and so on until we had selected our top 25. The votes can be redone, too, as Committee members are permitted to change their minds.

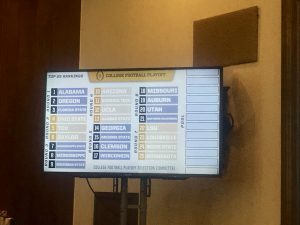

Four hours and a few spirited debates later, we had picked matchups and settled on our rankings. The mock committee’s top 25 teams for 2014 appear below, juxtaposed with the actual committee’s 2014 team selections. I felt validated to see our decisions weren’t much different than those of the real committee.

| COLLEGE FOOTBALL PLAYOFF SELECTION RANKINGS – 2014 | COLLEGE FOOTBALL PLAYOFF MOCK SELECTION RANKINGS – SEPT. 27, 2019 |

|

|

It’s worth mentioning that anybody can access the selection protocol. It is published in its entirety on the CFP website. It’s surprising how few people understand how the selection committee makes its decisions, considering its members, voting process, and rubric for ranking teams are readily available to the public.

Many selection processes in sports go by a simple majority among people casting individual votes. That the CFP requires consensus and embeds discussion and debate in the process speaks to the strength of its system of checks and balances. College football fans may grumble about the committee’s picks, but these critics fail to recognize how thorough the selection process really is.

For instance, the question of how to rank TCU and Baylor, which filled our No. 5 and No. 6 seeds respectively, provided fodder for our first debate of the morning. Both teams lost only one game in 2014. Although Baylor beat TCU in their head-to-head game, TCU also beat West Virginia–the only team to which Baylor lost. Head-to-head results typically function as a tiebreaker in these situations, but, upon considering the close score (58 – 61) of TCU’s game against Baylor, we decided to place TCU in the No. 5 seed and Baylor in the No. 6 seed.

It’s not uncommon for sports organizations to tout the credibility of their own decision-making processes, but relative to FIFA’s bidding procedures to host the World Cup, or the NCAA’s March Madness picks, the College Football Playoff operates with a remarkable degree of transparency.

For one, the College Football Playoff is an independent entity that is separate from the NCAA, the organization overseeing college football. This differs from the way March Madness operates, as the NCAA has its own Division I Men’s Basketball Oversight Committee decide which schools participate in the tournament. The NCAA does not employ an independent group to select and rank the basketball teams.

In addition, members of the CFP selection committee do not receive compensation and are merely reimbursed for travel expenses, while members of the Division I Men’s Basketball Oversight Committee are paid for their job of selecting and ranking the teams. That the CFP removes money from the equation makes its decisions less susceptible to outside influence.

Hancock takes pride in how transparent the CFP selection process is and said his favorite part about hosting the mock events is showing people what goes on under the hood. Perhaps as an organization, and a fairly new one at that, the CFP feels obligated to help students and members of the media understand what goes on behind the scenes. That the CFP does this is notable and fairly unusual in the world of college sports. Many basketball fans enjoy drafting their own brackets for March Madness, but the NCAA doesn’t exactly invite cohorts of journalists to their headquarters to witness what the school selection process for the tournament is like.

“We’re opening the curtain to let people see how things work,” Hancock said. “I like the fact that we can be open and have others experience what the actual committee discussed.”

For more stories from Cronkite News, visit cronkitenews.azpbs.org.